From the Boat Arts Centre again in the heart of Athens in Kypseli with Mustafa and Moody: we talk about racism in Greece, Mahmoud Darwish, normalising pushbacks and genocide, writing as witness, collective liberation, Moody reads his poem ‘Borders’ and Mustafa reads his ‘Kanoon’ (‘ كانون’).

‘We grew up with the – ‘there is a better life in Europe’ – so you want to leave this place, you want to go there, but the reality shocks you in so many things. There’s not only one border, there’s so many others.’ – Moody

‘Because the system is like that. So if you’re comfortable in your life and you don’t really care and you’re silent about an oppressor…and you don’t talk – yes, you take a big part of that responsibility. A big part of that blame.’ – Mustafa

Thanks again to the Boat Arts Centre for giving us this space and to the Arts Council of Ireland – without whom I couldn’t do all this. I just got some good news that the Arts Council are going to fund another season of Wander – so again a massive thanks to them for this!

Thank you all for listening to this season of Wander – and especially to all the poets who talked to me and shared their work.

previous episode Iman Ali Doosti // start of this season: Marwan Makhoul

Mustafa & Moody Transcript:

BAIRBRE:

Hi and welcome to Wander with me, Bairbre Flood, and with thanks to the Arts Council of Ireland for funding this podcast.

Today we’re coming from the Boat Arts Centre again, from the heart of Athens in Kypseli. In the last episode we talked to Iman Ali Doosti, one of the co-founders of the Centre, and today we’re meeting Mustafa and Mahmoodi, aka Moody.

MUSIC

MOODY: We grew up with the – ‘there is a better life in Europe’ – so you want to leave this place, you want to go there, but the reality shocks you in so many things. There’s not only one border, there’s so many others too.

MUSIC

MUSTAFA: Because the system is like that. So if you’re comfortable in your life and you don’t really care and you’re silent about an oppressor…and you don’t talk – yes, you take a big part of that responsibility. A big part of that blame.

MUSIC

BAIRBRE:

I start off by asking Mustafa what’s it like for him to write in English rather than in his native Arabic?

MUSTAFA:

As a second language, yes it is really tricky, but at the same time it’s a place that I’m trying to explore. Only if you get out from your own native environment and try to do that in the second environment, you’ll have a different perspective and point of view to it.

If you think about it, it is one of the oldest ways for humans to express themselves through metaphorics, you know, and this is why the perspective and the points of view, like, highly matters because it’s a metaphor, so according to the reader and the listener can be completely two different things, but then it all works the same way.

BAIRBRE:

Sure, and I think that’s where sometimes as well the political aspect can come in, because you can say things that are deeply radical in a way that it’s like getting people to look at things completely differently, which is part of the whole politics of change, and like we were talking about Mahmoud Darwish earlier…

MUSTAFA:

If you bring on Mahmoud Darwish, this man is revolutionary, you know, it’s pretty much, he had managed to transform all the suffering of a lot of the Palestinian people into art.

And this is an incredible achievement because to witness your own people dying and you go through that and then at the end you transform it to art – it’s a sacrifice in my opinion, because you are taking all of this pain on so that you can put it in a form of art that could be listened to and to have the attention towards the suffering of your own people, so that’s why in my head Mahmoud Darwish is a revolutionary.

I hope that he would still be with us now, actually, in the light of the genocide that is taking place in Gaza now, this could have been, yes, maybe I would say it could have taken a different side, you know, from the outside group.

MUSIC

MOODY:

The same as Mustafa, I’m from an Arabic background, even though my parents are from Somalia, so you can add to it, like, third language, so if you were speaking about writing, it would be, like, even more, like, so many different cultures together, which makes it also, like, a little bit difficult to focus on one.

The main one now, I would say, is Arabic, like, if you think, you will think in which language, this comes as a question, right, so I usually think with Arabic language, but, like, the last five years, I would say six years, English is going in as well, and mostly when I write something, I write them in Arabic, then translate them to English, as we said already, it lost its flavors, let’s say, right, but you still try to find them back to write, like, to make them with a good scheme.

BAIRBRE:

And do you ever publish anything in Arabic, either of you?

MUSTAFA:

No, I don’t really publish, that’s the thing, you know, the only time when I share is in these kind of settings, or a night of poetry over, yeah, food, or, you know, just people sitting together, hanging out, and at some point, hey, let’s read some poetry, or do something, or, like, right now, for example, like, right now, yeah, exactly, in this kind of setting, so, no, not really, it’s not, like, yeah, no, I don’t publish, you know, a lot of things, also, we write, I believe, Mahmood as well, here is, it’s quite personal, you know, so it takes so much, like, a significant amount of courage to put this out, you know, and a lot of things that might be controversial, as well, to some readers, so, it can be, yes, to write just for the purpose of feeling it, yes.

BAIRBRE:

I got you, that’s fair enough, that’s, yeah, fair.

MOODY:

Yeah, exactly, the same, we just write when we have, like, the chance to write in gatherings like that, but as he said, like, it’s more personal things that we both write, we have, like, our, some jam sessions we do, like, music jam sessions, and we write on the spot, not prepared at all, just, like, going there, writing some stuff, and singing, and that’s how I know, how I found out that he writes, as well, and then, when I read what he wrote, I was, like, yo, you’re talented, man.

BAIRBRE:

That’s lovely, you have a nice connection, creatively.

MOODY:

Yeah, yeah, yeah, bro’s talented.

BAIRBRE:

He has to say so as well, I think.

MUSTAFA:

Yeah, 100%, and it’s really interesting to find, you know, so, okay, same base of Arab culture, but complete two different countries, and complete two different environments, you know, so, to be able to come to a point where you have so much in common with a person, you know, I mean, like that, it just can only say that it’s clear evidence that we are all the same, as children, we all, like, we all run after cats, you know, so it doesn’t matter what colour you are, and where you, you know, so this is one of these, like, concrete evidence that, really, there’s no difference, you know, so to find that connection with someone that you really didn’t grow up with, though it feels that you did grow up with this friend, you know, and together, it’s…

MOODY:

The same childhood music, the same, like, the first time we sang that song, it was, like, some childhood memories he brought back, and he’s from a totally different country, right, Iraq and Saudi Arabia, Somalian and Iraqi, but we are singing the same song, and then, like, the other one, oh, you know that one as well, you know that one as well, so it’s, as he said, like, seems like we were, like, we grew up together.

MUSIC

It’s titled ‘Borders.’

No matter how perfect our lives may seem, we gotta remember that others have dreams. Lives intertwine with joy and with pain. We are not alone.

Others share the same reign. But are some of us free, or are we all trapped? I hope at least we acknowledge the boundaries dividing us, the level of privileges.

Can’t count them all in one hand. Gender, sexuality, or religion. And the lines that are drawn in the sand.

You could be killed just because of the color of a skin, or live the best of your life because the type of the passport. Where do we begin? Just a piece of a paper, a mere document.

Why does it separate us, create such a torment? When shall we unite? Where is the equality to break down the walls that lead to disparity?

People fleeing shadows that cloud their days, hoping for a light on the other side of the sea. They cross into borders, searching for peace, and yet face other barriers never thought they exist.

Camping on a Greek island in the summer, warm glow? Seems so romantic, huh? But is it though? Yeah, I mean, it is, if there was a choice.

But in a tent, winter, cold? You came and you thought your type in here have a voice? Torrential rain, you shivering, confined in a small tent.

Can’t feel your feet, but by the way, we have given you small blankets. It’s alright, you’ll be surrounded by mud next morning. Yeah, those days we have survived.

But what’s left for exploring? We took one more step with every passing moment new borders arise. Colors, face, shaping societal ties.

Facing judgmental eyes, what if name Mahmoud that carries the weight? Or Mustafa on application, the job seek, still bound by fate? No, we cannot change our color or creed, yet can we break free from this systemic greed?

How many more borders will we have to face? Where is the dreamland to seek refuge? Or it’s all nightmare when I think of Greece.

Now, how many more fights we will have to lose? Being united is a dream faded away, and it’s a hope that lost its light. Now, we search for a connection, an ocean of struggle.

Yet the borders still linger. But anyway, it’s a losing puzzle.

The borders will hold us back.

And it will always have us blind.

MUSIC

MOODY:

We are all the same people, but we grow up, we find out there’s more barriers.

Crossing borders is not enough.

MUSTAFA:

Yeah. You spoke about camping in the summer in the Greek island. Is it romantic?

Yeah, I like it. I just say I like it, you know? I mean, look, it was, it was terrible, but there was a great sense of community also.

And, and that, and that for me, that is the privilege, because, you know, speak about white privilege, it’s something that is really fragile, because people, if they were born privileged, and they carry on being privileged, and if that thing was so normalized in their life, and it was taken away, it would be, yes, a big loss. Because, you know, like, people are going around with a big thing, you know, a big fear of losing something, you know, that is there. Whereas if you were born without, with no privilege, it’s not, it’s not your choice.

It’s the system, right? But here comes the other adaptation, which is, you know, you’re also born with more resilience. And that’s something we have to consider.

You know, I’m trying to be a bit, like, positive about this, because, because yes, that’s, that’s the thing, you know, it’s like a person that was born blind, obviously, they will adapt to other senses, you know what I mean? It is like this in my head, the same way, the same way I think about privilege. It is, but there are ways around it, you know, I would like to be stopped racially profiled in the airport every time, you know what I mean?

I don’t need to hold a book in my hand every time I go to the plane, wear glasses, you know what I mean? To show them that I’m the good refugee, you know?

MOODY:

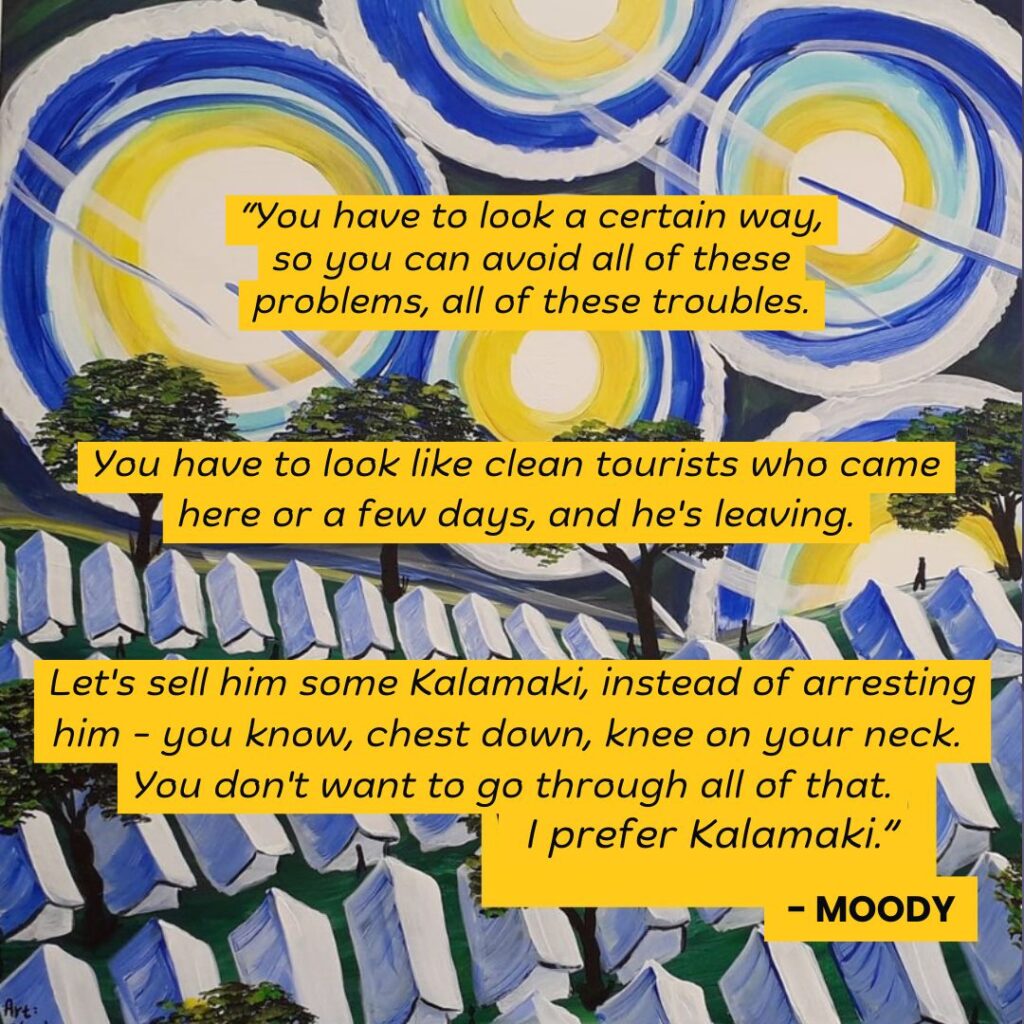

It’s very difficult. And you have to look a certain way, so you can avoid all of these problems, all of these troubles. Like, you have to look like clean tourists who came here for like a few days, and he’s leaving.

Let’s sell him some Kalamaki, instead of, you know, arresting him, you know, chest down, knee on your neck. You don’t want to go through all of that.

I prefer Kalamaki.

MOODY:

Yeah, we grow up with like, there is like the future in Europe, like there is the better life in Europe. So, you want to leave this place, you want to go there, but the reality just shocks you with so many things. Yeah, there’s not only one borders, there are so many others to cross too.

And we, I mean like, if you cross borders once, Mustafa, we have to keep going. More borders. But I think the others are like, uncrossable, you know?

MUSTAFA:

This thing just happened today, man. I was walking across the street, and there was this old woman, I mean, not so old, I mean, how can I say this?

Old enough to understand that life is, you know, it’s a bit not fair, you know?

So anyway, she just walked past me, and then the moment that we passed each other, she put her hand really tight on her purse, you know. And the moment we passed each other, I look back, she released.

Okay, that’s okay. But you don’t have to show me that so much. And it’s something we learned.

A lot of us learned, because we cannot, of course, generalize the situation. People are different. And there is a lot of layers of racism and a lot of levels.

And some can be understood, and some can never be justified. So we are also people of, we try to be people of critical thinking of ourselves as well, and the others, and try to wear the shoes, and try to understand why these acts are taking place, you know? But this doesn’t deny the fact that in a bit of tiny moment, I was a bit hurt.

And many of us are like this. It’s just really difficult not to take it personal, when it is like that. And especially when you sit on the train, always the hands up.

MOODY:

You’re holding your backpack like this in your hands, or like at least, always keep your hands up. It doesn’t mean that you will steal something if you put your hands down, but like the look that they give you, the people, like they’ll check your hands, you know? Where are your hands?

Okay, his hands are there. So they are okay.

One more thing is, you always have to look clean. You have to look like you’re most beautiful all the time. You have to look like you are a tourist, so the police don’t stop you.

You can’t just get yourself comfortable, like in the most comfortable clothes just to go to the market, especially if you live in this area, keep silly around, because the police will always stop you. You have to look a certain way, so you don’t have a bad day. And that’s it.

BAIRBRE:

It’s just shitty, isn’t it? Malakas, like what the fuck.

MUSTAFA:

You gotta erase that part!

BAIRBRE:

But it is hurtful.

MUSTAFA:

Yeah, we joke about it, you know? We keep a track of, hey, how many times you got protected on, you know? This is, yeah, we talk about it, actually.

It’s in a form of a joke, because there’s no other way. You gotta make a joke out of it.

And also writing, yes, it’s where it plays this really important role.

BAIRBRE:

For sure. Would you read me a piece, Mustafa?

MUSTAFA:

I could read you a piece, yes. Okay, so since you spoke about the camps and the asylum system in Greece, I would like to put the light also on another struggle, which is detention centers. This is a whole different reality of the camps, you know.

Two brothers, okay? And one of them is a minor, just to give a bit of background. And the other one is an adult.

And this kid is a minor, so he registered as an adult, because he thought if he registered as a minor, he would be separated from his brother.

MUSIC

Kanoon

Kanoon fell on the bank of the other world, ended where he started.

Nothing was left of the dreams that have passed

but the smell of fire and waiting.

But how did he end? Was it the inevitability of fate?

Or was it the randomness of choices and injustice?

In worn-out shoes and an oversized dirty coat,

lifting a food card in his hand, he shouted and repeated,

I am 12.

Until that has become his new identity.

Behind the fence,

there were guards in clean clothing

giving out moldy food

at the directorate of the pre-removal facility of detention.

From a minor, I became an unemployed man

who never enjoyed the luxury of making decisions.

He walked and kicked a stone,

avoiding thoughts of what was to come.

Rami wake up, I brought lunch.

In a disconnected, annoyed voice, he replies,

how many times I told you, don’t leave the container without telling me.

He took his chair and sat by the container entrance.

Having left some moldy food on the ground for friends,

he held his share of bread, smelling it,

trying to track back a memory of his mother’s baking during the days of sage,

biting on it and sharing the crumbs with the rats.

Kanoon shouted again, 12.

An officer approached.

Come with me, the officer said.

I need to tell my brother.

Rami was still on his bunk bed and hadn’t touched his food.

No, the officer said.

The gate was open.

After leaving the facility, the happiness of his younger years have returned.

They placed him in a car and drove away.

He thought his brother was in one behind him.

He got out of the car.

The place seemed so familiar.

His heartbeat sped up.

Have you seen Rami? He asked around.

No one answered.

They forced people to strip naked

and abandon whatever belonging they had left.

Kanoon did what he was ordered

and shouted for his brother,

shivering from cold and confusion

until he fell back on the other side of the river.

MUSIC

MUSTAFA:

So this guy was 12 years old and that’s why his character name is Kanoon, the 12th month of the year.

His food card actually was also number 12, you know, and he was the only one that had the food card number 12 in detention and everybody calls him 12. They don’t call him with his real name. Eventually, this had become his really new identity.

One day, this is a continuation of the story of the brutality of the system and the Greek police in Europe in general when it comes to that. So, you know, the story went well. He was reunited with his brother again and they were about to go and receive their travel documents and residence permits, you know, after being granted asylum here in Greece.

So everything was great until the day before or a few days before he goes and picks them up from the service. He went outside in the park to play with his friends and then he was kidnapped along other people by the cops and then he was pushed back to Turkey and this is when he fell on the other side of the river and now he is in Turkey.

MOODY:

So he was arrested when he already had, like he has a document, like he had ID – was waiting for the travel document to come out.

MUSTAFA:

Yes, look, he went outside the park as any other kid to play, not thinking that he has to have his papers on him, you know. So he went outside without any papers on him. He’s just a kid, man.

But he has, yes, he’s a recognized refugee. That’s 100%. He’s only waiting for the ID and the travel document to go pick them up in the next days.

And yeah, so because the fact that he was in the north and it’s close by, you know, the Turkish border is way easier for the police to kidnap people like that and push them back, you know. And well, he made it back, you know, like probably thanks to the people that were with him. Also, they were pushed back, you know, and they were stripped from all of their belongings.

But now he’s in Turkey and his brother have left Greece because he could no longer live in Greece with this reality. And he’s now in Germany and trying to be reunited again with his brother. So the guy, he registered as an adult so that he won’t be separated.

But at the end, he was separated, you know.

MOODY:

So the brother got the travel document, like both were waiting. One was pushed back just days before they receive it. The other one got the document and went to Germany.

And one is stuck in Turkey right now. Yes. That’s crazy.

But also knowing that you’ll be pushed back even though you’re recognized, could be you tomorrow, you know what I mean? Could be any of us.

MUSTAFA:

Yeah, that’s, yes, that’s the reality of things, you know. The illegal pushbacks are happening and taking place quite often, more often than we all think. And, you know, just if you also try to read about it, there’s a lot of media about it.

This journalist from, sorry, this journalist from Australia, he did this investigation. He followed a family from Somalia, actually, in Lesvos Island. And I think it was a family of 10 people.

If I, you know, could correct this information also. And he documented everything on camera, the whole process of pushback, you know. So there was very clear evidence that the Greek police is doing this.

MOODY:

Yeah, I was shocked when I know that they will push back when people arrive first, like arrivals, the boats, they push them back or like push them back in the middle of the sea. Yeah, that was shocking in the beginning. But knowing that even though you are recognized, then you’ll be like a new story.

This for me is, but anything, anything would be normalized tomorrow. So we are as a human, we’re just getting used to the things happening to us. And tomorrow, everything will be normalized.

Like now it’s pushbacks are normalized. You know, people are getting used to it.

BAIRBRE:

Genocide is normalized.

MUSTAFA:

One of the biggest powers that all of these regimes would have is the silence. And if there’s only a few of us talking, they could 100% cover that out. You know what I mean?

So yes, I can put also a lot of the blame on the people because the system is like that. So if you’re comfortable in your life and you’re happy about, you know, your life, and you don’t really care and you’re silent about an oppressor somewhere else or here or there and you don’t talk – yes, you take a big part of that responsibility. A big part of that blame.

MUSIC

BAIRBRE:

Thank you so much for talking to me. Yeah, thank you.

MUSTAFA:

Yeah of course. And let’s hope for a collective liberation in this world.

BAIRBRE:

Inshallah.

MOODY:

Thank you so much. And also for giving us space to share how we feel about all these things happening – and yeah really grateful for all of this.

BAIRBRE:

A huge thanks to Mustafa and Moody for sharing their poetry and their knowledge with us – it was a lovely conversation and I really hope to hear more of their writing in the future!

Also thanks to the Boat Arts Centre for giving us this space – and to the Arts Council of Ireland – without whom I couldn’t do all this.

I just got some good news that the Arts Council are going to fund another season of Wander – so again a massive thanks to them for this!

I’ll be starting this new season very soon – will keep ye updated on the social channels – @bairbreflood (that;s bairbre the irish spelling – bairbre) and we’ve started a Tiktok channel so if you’re on Tiktok come and subscribe there too – again @bairbreflood

And if you want find out more about the Boat Arts Center their website is theboatcollective.org

Thank you all for listening to this season of Wander – and especially to all the poets who talked to me and shared their work – please go and check out more about any of these artists at bairbreflood.org

Ok, talk to ye all soon, have a great autumn and bye for now!